A timeless tale of personal, social, and environmental urgencies: An Excerpt of In the Bear's House by Bruce Hunter

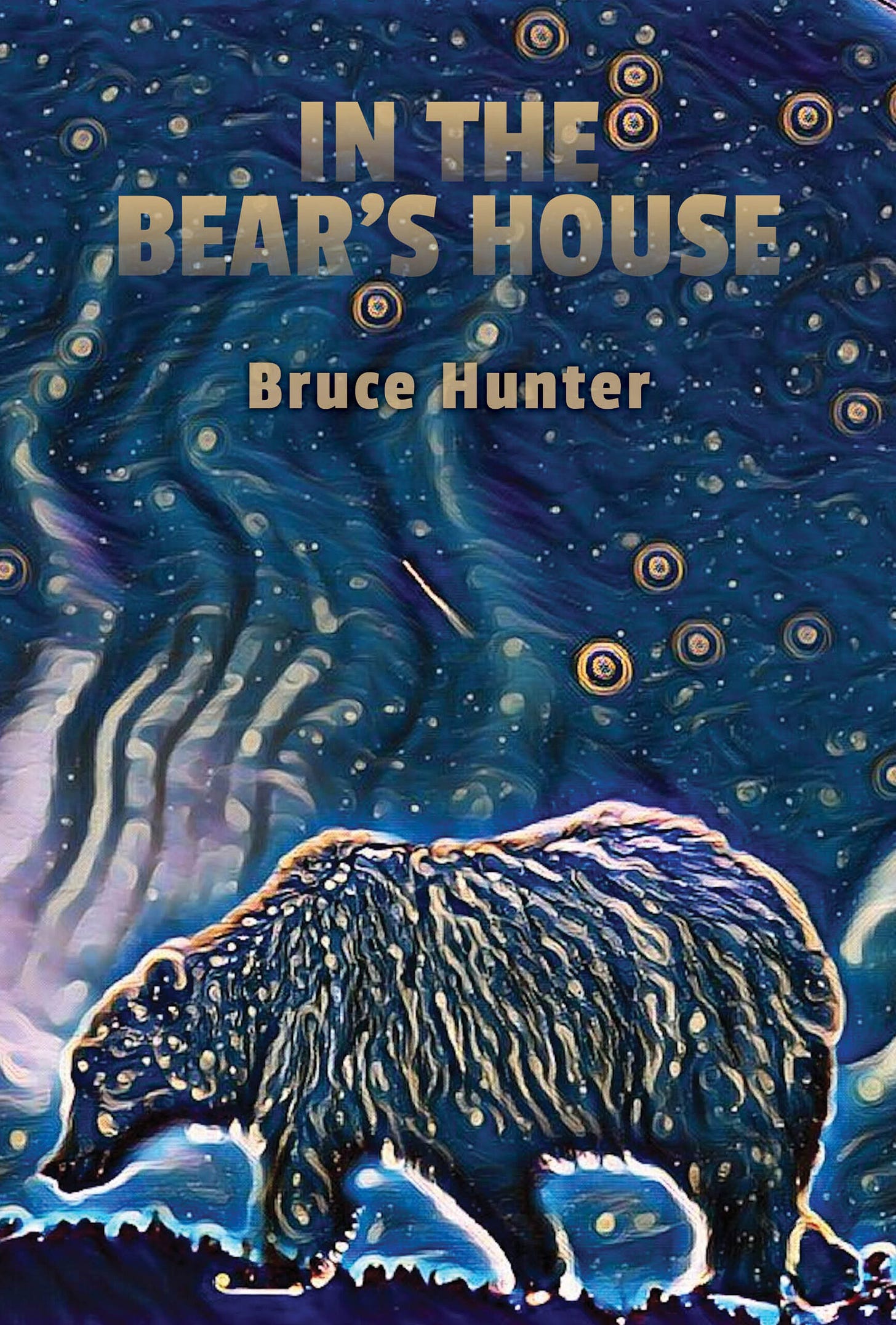

Preview a new edition of Bruce Hunter’s award-winning novel In the Bear’s House from Frontenac House Ltd.

Hi friends,

For today’s post, writer Bruce Hunter has shared an excerpt from his recently re-released novel, In the Bear’s House. It’s available from Frontenac House Books.

Here’s one of the blurbs from the new release:

In the Bear’s House is an enthralling novel of struggle, love and hope for the land that is home to both Indigenous and non-indigenous people. Bruce Hunter’s compassionate intelligence and stylistic prowess combine to put the reader directly in touch with fully fleshed characters in the rich and rocky territory of their lives and time. Set in working-class Calgary and the Kootenay Plains of west central Alberta, In the Bear’s House alternates between a mother’s story (voiced intimately in first person) and her deaf son’s tough coming-of-age story. Hunter captures the intricacies of gritty family life alongside a vivid portrait of the 1972 Bighorn dam project that gave no consideration to human and environmental costs. Acutely observed, deftly detailed and poignantly told, In the Bear’s House is a timeless tale of personal, social, and environmental urgencies. A deeply humane novel for the ages.

— Elana Wolff, author of Faithfully Seeking Franz and Everybody Knows a Ghost

In the Bear’s House, Chapter 1: Clare

Bruce Hunter

He was my first-born, my blue baby, my water baby. Before all the others came, passing from me in a rush. At first there was no indication of anything wrong. I suspected nothing, although I’d heard things from my grandmother on my mother’s side — Grandma Locke, “pronounced like lucky,” she’d always say.

“Tha wee bairn,” my grandmother cooed when she held him the first time, already a damp red curl on his head, “he’s a bonny wee lad, wha’s dead couthie an’ greets a’ thae while if he’s nae cuddled.” I’d no idea what she meant, and my Uncle Jack shrugged, but Mom laughed, the three of them with me in the maternity ward that day. Mom translated, “He’s cute and cuddly, but if you don’t hold him, he’s gonna cry on you.” Grandma Locke warned me too of the mark of Cain. And she told ghost stories, which as a girl I laughed at, although I told her nothing of the ghosts I’d seen. As if admitting made them real, and the old country our family left, no longer old or far behind. His was not the mark of Cain, but another, as we would soon come to know. For a family named Locke, like lucky, we often weren’t.

I’m not sure whether water was drawn to him or he to it. But as the doctor held him up for the first time, and the nurse cut the cord and whisked him from my sight, his blue skin, congested face and maybe most of all, his silence, terrified me. Through the daze of his birth, I could hear the quick clipped smacks on his bottom, the hiss of the oxygen tank behind the curtains, and then his wailing, high-pitched screams, broken by gurgles and little gulps. He was breathing — and I would never again be so happy to hear a baby cry. He was born at 5:29 in the middle of the third week of May 1952, just as the sun sent its first dusty light through the corridors of Calgary General and the city below stirred in its final hours of sleep.

Will was my first, and for the rest of his life, he woke before the sun. Only my mother, her oldest brother Jack, and my grandmother came to see me in the maternity ward. My dad left a long time before and my husband was in prison. Mom had two outfits on the go, made from some baby blue lambswool her boss had given her — she worked as a housekeeper and seamstress for a Jewish family in Mount Royal and sometimes she helped out in one of their stores. She made all our clothes. We lived in a rented farmhouse in Homepatrick, six blocks past the end of the Killarney bus line, out on the prairies near the Sarcee Indian reserve.

Lowell and I got married the previous November at old city hall. I was seventeen. He was two years older and neither of our mothers approved, but I’d already miscarried once with his child, at fifteen, and I knew this time there was going to be a baby. And we knew Lowell was going to jail. He’d committed a serious crime. I was two months pregnant when he was sentenced, so his mother and mine had no choice but to let us marry. Lowell’s mother wanted nothing to do with me and blamed me for everything that happened to him, though his troubles started long before I came along.

At the end of May, I carried my baby home. Mom gave up her room with her treadle sewing machine, button boxes, and bolts of fabric. We did have a furnace but no running water. There was a hand pump by the kitchen sink and a privy in the backyard. Those old houses had only horsehair or newspaper insulation and that winter, when I got up to feed Will, I dusted off the thin layer of snow blown in across the covers of our bed. That year snowbanks covered the Banff Coach Road winding up the hill past the country radio station Mom listened to, all the hurting and mournful songs I hated. My grandmother assured me it’s not the curse, but how we live. How you stand up when you fall down, she’d say. I scoffed when I first heard that.

The cursed know their lot, she claimed. The scattered thoughts of an old woman, I thought. It was certainly not what I believed as I shook the snow from my son’s blankets. I wondered what we’d do, this baby and me. Not what would happen to my husband. That was decided by the judge. And for two long years, Lowell was sent away. I wondered what would become of us.

More about In the Bear’s House:

In The Bear’s House by Bruce Hunter Set in 1960s Calgary and Alberta’s backcountry, this reissue of In the Bear’s House tells the story of a creative young mother, Clare Dunlop, raising her deaf son against the insurmountable odds of poverty, mental illness and hardship.

The novel opens as seventeen-year-old Clare gives birth to her son, while her husband serves a penitentiary sentence for a serious crime. After contracting pneumonia, her infant son loses his hearing.

Later, the young boy, nicknamed Trout, struggles to find his way until his 99-year-old auntie gives him a conch shell. For Trout, the conch becomes a literal and metaphorical hearing aid. He cannot hear the sea in the shell. Instead, he hears the mad swirl of the adult world around him full of contradictions and deceptions. Out of chaos, he finds clarity.

At the death of his beloved auntie, Trout spirals out of control, getting into serious trouble at school and at home. His mother, challenged with chronic depression and the impending birth of her fifth child, sends 12-year-old Trout to live with her deaf uncle, Jack, in the wilderness of historic Kootenay Plains. There, Trout thrives, finding adventure, connection, and belonging, with his forest ranger great-uncle and his musician wife. Trout learns the wisdom of survival, listening and observing, from the elders of his own Scottish clan and those of the nearby Îyârhe Nakoda. He bears witness to land theft from First Nations to build the controversial and environmentally ruinous Bighorn Dam.

Despite its devastating sociological and ecological impact, the dam becomes Alberta’s largest reservoir and hydroelectric plant. Trout sees what others may not. Both the rugged beauty of the land, and especially its people, the destruction of their sacred places. homes and livelihoods. Disability becomes an unexpected gift of insight. In the Bear’s House is ultimately about listening to the wild and the wilderness, and what we lose when it’s gone.

Bruce Hunter is an active writer, speaker and mentor. His award-winning novel In the Bear’s House was just rereleased by Frontenac House. In 2024, as Nella casa dell’orso, it was published in Italy, as was his 2023 poetry collection Galestro, following, in 2022, A Life in Poetry, Poesie scelteda, and Two O’clock Creek, all by iQdB edizioni. In 2021, his memoir essay “This is the Place I Come to in My Dreams” was shortlisted for the Alberta Magazine Publishers’ Awards. In 2024, his eco-poem “Dark Water” won the gold prize for poetry for the same awards. Bruce’s poetry, fiction, reviews, interviews, translations, and nonfiction have appeared in over 100 publications internationally. Website: www.brucehunter.ca

Subscribe to see more guest posts from WRJ’s amazing contributors / Paid access includes editorial feedback for 1 poem each month, Q&A with the editor, and more.