Building an Archive: How to Read and Organize Your Notes For Better Writing

A guest post from Kasey Butcher Santana

Hi friends,

It’s time for another guest post, and this one continues the theme of highlighting the wonderful contributors of WRJ’s new(-ish) Winter issue. Today, Kasey Butcher Santana offers her take on “building an archive” and keeping our reading organized to help us write!

Here’s an overview from Kasey’s website.

I am a writer, alpaca farmer, and backyard beekeeper. I earned a Ph.D. in American literature and have worked as an English instructor and a jail librarian. I am currently working on a memoir in essays about these experiences and regularly write about the environment, mothering, grief, bees, and other curiosities.

I am also a volunteer docent at Denver’s historic Molly Brown House Museum and active with my local Citizen’s Climate Lobby chapter and the Environmental Voter Project. I am Nonfiction Editor for Kitchen Table Quarterly.

Be sure to have a look at all of Kasey’s CNF piece “Collecting Fabulous Trees” in the Winter 2025 issue, as well as “The Homestead After Dark” from Issue 23.

Enjoy!

Building an Archive: How to Read and Organize Your Notes For Better Writing

Kasey Butcher Santana

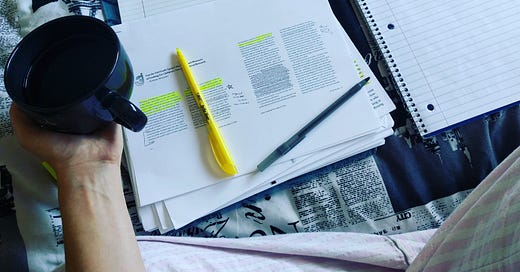

If you close your eyes and picture how you have stored information, do you see a messy filing cabinet, a cluttered desk, or a perfectly shelved library? I would never shame you for a messy desk—mine is covered in Post-its—but I have spent much of my adult life in libraries, so when I read the advice that writers must read widely, I want to butt in and ask how they are supposed to organize that reading. Whether it’s a cluttered antique bookshop or the Library of Congress, build yourself an archive when you read and you will develop more in the process.

Build an Archive

Before I started writing creative nonfiction, I completed a Ph.D. in American literature. In the process, I had to create three reading lists. First, to complete my master’s, I was required to pass a comprehensive exam covering a reading list in two parts: an Area of Study and a Special Topic. Then, to mark the transition from coursework to writing my dissertation, I had to pass another, more intense comprehensive exam, covering a bigger reading list in two parts. Finally, for my dissertation prospectus, I provided a working bibliography, which would be covered in my dissertation defense.

My brilliant dissertation advisor described these lists as “building my archive,” putting my research in the context of other scholarship and literature relevant to questions I was trying to answer. I often think about that image as I work. How am I building an archive for the questions that interest me in my writing today?

Reading by Topic

As a Doctoral Candidate, building my archive was about establishing an area of expertise. Now, I think of my archive as a reservoir for curiosity. I keep track of the latest work on subjects I tend to write about. I am also intentional about notetaking. More on that later.

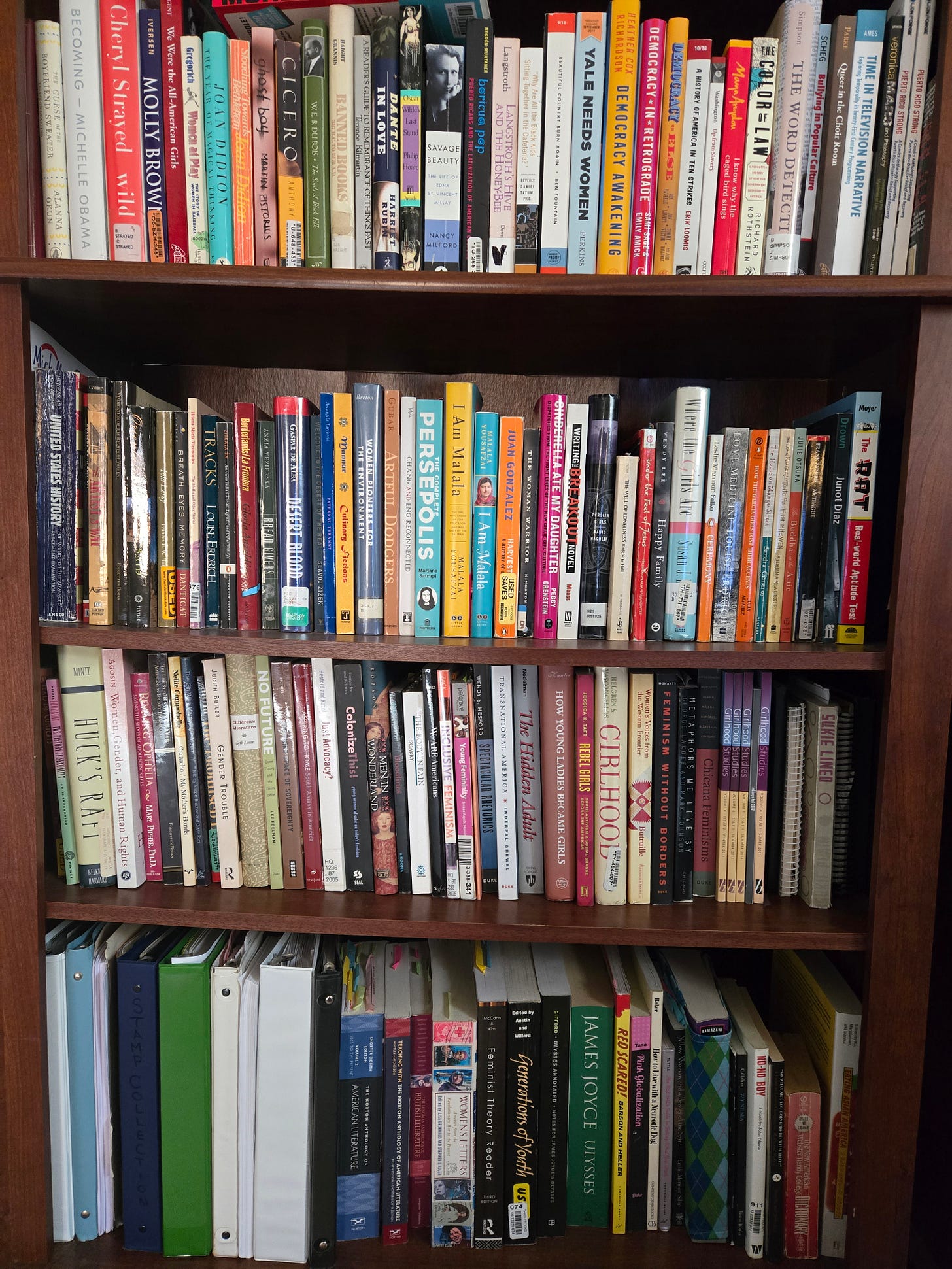

Sometimes it is necessary to read for depth, not breadth, expanding a shelf in the archive for a specific subtopic. For example, maybe you generally keep up on nature writing, but you want to write about trees and need to develop a nuanced understanding of how forests grow.

The library is helpful for this type of reading. Head to the library to browse the shelves, which are usually arranged by topic. I start with one book I located via the online catalog and then look at what titles surround that book. Recently, my daughter and I wanted to learn more about mushrooms so we went to check out Mushrooming by Diane Borsato. We left with a dozen books ranging from illustrated guides to memoirs on the expanding field of mycology.

Reading for Style

We do not always read to find information. An archive of writing you admire for style, genre, or technique helps guide you as you craft your voice or inspires you when you do not know what to write. This archive also turns your leisure reading into a resource without much extra work.

Reading for style can be more exploratory, crossing genres and subject matter beyond what you typically write. As you read, if a style element, technique, or image excites you, jot it down. Read your influences and make notes on what specifically inspires you about their writing. This practice helps a writer keep track of what they are learning about writing as they read, creating an archive of memorable passages from other writers. Over time, you may notice trends in what writing moves you.

Organizing Your Archive

I have always been a pen-and-paper kind of thinker. I organize my home library by genre and subject, keeping books I am using for research close to my desk. In grad school, I kept binders with pages of annotated articles, hand-drawn charts, and plenty of angst in the margins. I had classmates who swore by software such as Evernote or Scrivener. I knew someone who used Pinterest to organize research. Whatever works best for you, lean into that style. I wrote on my Substack about keeping a daily notebook, but I find two methods most helpful for organizing my archive.

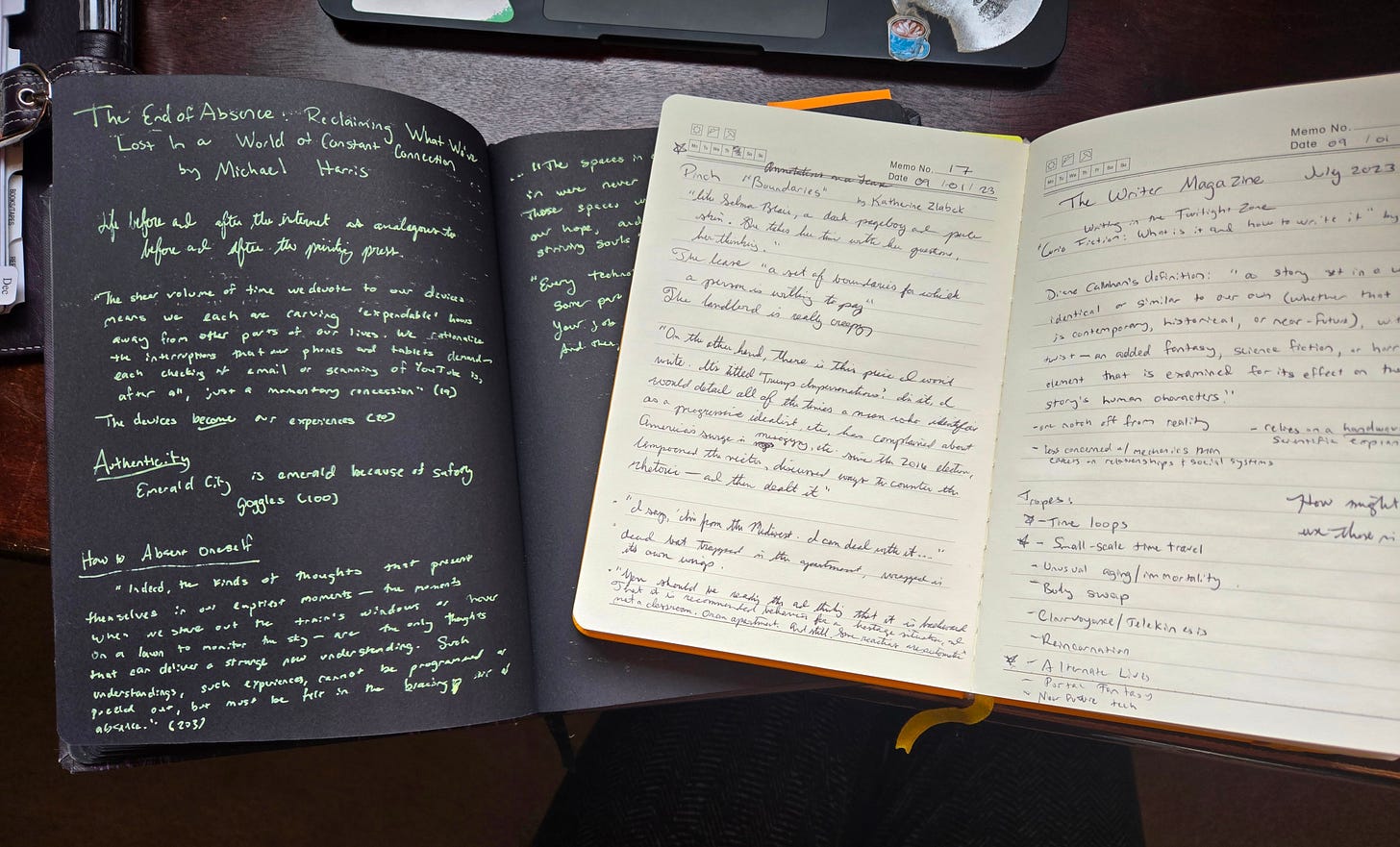

A Reader’s Journal

I keep a notebook in which I catalog what I read in literary magazines and jot down evocative passages. This practice has helped push me to experiment more and has been useful for understanding what styles and subjects different magazines prefer when I work on submissions.

A Reader’s Journal is like a scrapbook in which you:

● Log what you read by title, author, and date.

● Note thematic impressions, interesting creative choices, and details that stand out.

● Create sections for different genres.

● Use different colors of ink to highlight recurring themes or techniques.

This is an opportunity to use any fancy notebooks you have but are afraid to write in. Your notes don’t have to be pretty, they just have to be functional.

A Commonplace Book

Commonplace books are a more structured way to organize around a specific topic or project. Your Reading Journal may be more haphazard and freewheeling, but a commonplace book contains more thematic unity and organization. Notebook of Ghosts has an excellent history of commonplace books and examples of what they look like.

Some sections that a commonplace book for your archive may contain:

● A glossary of terms for your project

● Writing techniques and examples of them

● A bibliography

● Subtopics from your research

● Timelines or outlines of big ideas

● Charts of relevant data

I keep commonplace books by project. In a commonplace book for an essay collection I am writing, I keep brainstorming notes, quotations from research, and outlines for both the whole project and individual pieces. These notes cross-reference with my larger archive so that I can find what I need when I am writing. I also have a commonplace book for gardening. There are many uses for this type of notebook.

Where Do You Fit?

Think of the works in your archive as in conversation with each other—and with you. Modernists talking back to Victorians. Poets drawing on the scientists’ work for inspiration. Mycologists all voicing opinions on what is the coolest mushroom. Authors of scholarly work reference other researchers, sometimes building on their work, sometimes arguing with it, but writers of all genres talk to each other to some degree. How many Gothic novels have riffed on Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier? Mexican Gothic and Advika and the Hollywood Wives spring to mind. Creative nonfiction writers may converse with scientists, historians, and figures from our own lives.

Allison K. Williams recommends identifying comps for your work by finding what books would be shelved next to yours. As you build your archive, keep in mind the question of where you fit in the conversation. Ultimately, your archive not only helps you put your work in context and identify a market, but it also helps you develop a voice and a niche.

All photos courtesy of the author

Kasey Butcher Santana is a writer and caretaker of a small alpaca farm where she and her husband also raise chickens, bees, and their daughter. Kasey earned a Ph.D. in American literature and has worked as an English teacher and a jail librarian. Recently, her work appeared in Split Lip Magazine, Pithead Chapel, Write or Die Magazine, Superstition Review, and Five on the Fifth. You can follow her on Instagram @solhomestead or at Life Among the Alpacas on Substack.

Subscribe to see more guest posts from WRJ’s amazing contributors / Paid access includes editorial feedback for 1 poem each month, Q&A with the editor, and more.

This is super helpful, thanks!

“a reservoir for curiosity” — a perfect description