My Friend, Co-Author, Co-Editor, and Kindred Poet: Interview with Death Row Prisoner George T. Wilkerson

By Kat Bodrie

Hi friends,

It’s time to start thinking about gifts for the writer in your life. A gift subscription to the Wild Roof Journal Substack may be just the thing. Click here to get it set up!

Here’s this week’s guest post. It’s a powerful piece from Kat Bodrie, who graciously offered to share her interview with George with us.

My Friend, Co-Author, Co-Editor, and Kindred Poet: Interview with Death Row Prisoner George T. Wilkerson

Kat Bodrie

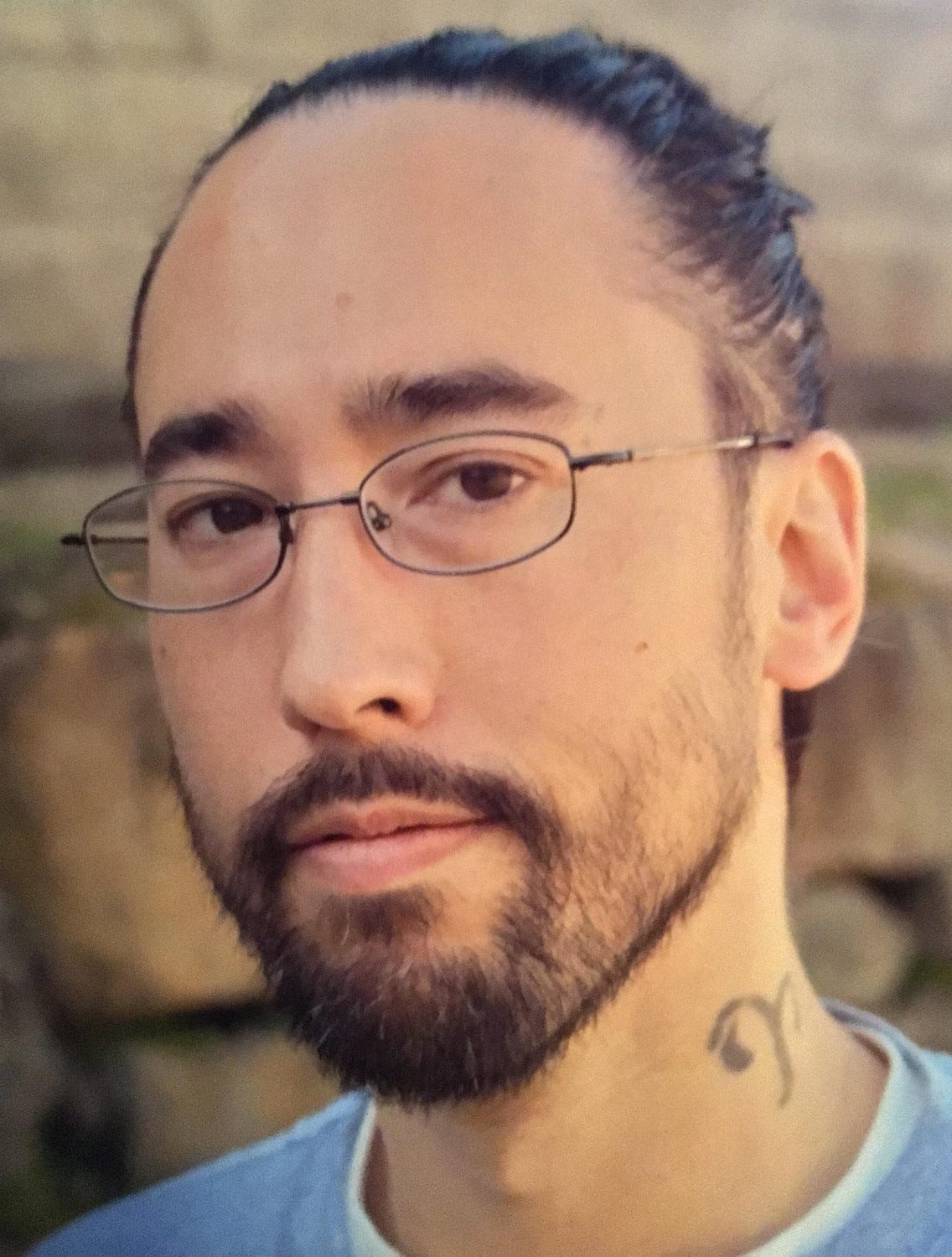

Before 2021, I never would have thought I’d be best friends with someone from Death Row, nor that we would be literary collaborators. But George T. Wilkerson is something else — friendly, funny, smart, and entirely self-taught.

He’s been writing since 2012, when he took a creative writing class that was offered for North Carolina’s Death Row prisoners, all of whom live at Central Prison in Raleigh. George had been a hardcore reader, like many in prison, but through the class, he learned how much he loved playing with language and how useful writing was for processing his difficult upbringing.

Around that time, he met Tessie Castillo, who would later be the editor of Crimson Letters: Voices from Death Row (or CL, for short), which he co-authored with three other guys on his unit. I befriended George through a book club Tessie offered via Zoom. Each of the men called into our group on different days, giving us the chance to ask questions, hear their voices, and learn more about them as individuals. CL was a collection of creative nonfiction pieces about the guys’ experiences in the free world and in prison, so it was news to me that George is also a poet.

A week or so later, Tessie asked for volunteers to send the guys their edited chapters for the second edition of CL (later published as Inside: Voices from Death Row by Scuppernong Editions). I volunteered, and along with George’s edited chapter, I sent him a letter and a poem of mine for feedback.

We formed a fast friendship based on our mutual obsession with poetry. I was impressed by the feedback he gave me, which was thorough and seemed to be from someone who had a degree in creative writing. He asked for feedback on his poems, too, and pretty soon, we were sharing almost everything we’d ever written, eager for the other’s ideas, edits, and validation.

George doesn’t have access to a computer or the internet. Beth Browne, his literary friend who’d been typing his poems and submitting them online on his behalf, was literally sailing around the world and had limited access to the internet herself. So, I picked up where Beth left off.

George and I also started collaborating on poems and books of poetry together. Our unpublished manuscript While You Worried about Toilet Paper combines poems each of us wrote, both before and after we met, and comments on the need for individuals to balance Self and Others. Our work-in-progress an/Other explores our differing childhoods and backgrounds and documents the way we’ve been able to connect and find similarities despite our differences. We also invented a new poetic form, which we call the triangulation poem, where three random things (usually from our recent conversations) are compared within a single poem. And in spring 2025, we’re rolling out the first issue of our co-edited lit mag called bramble online, with the tagline “poetry that sticks.” (Visit brambleonline.com for more info.)

This is truly a symbiotic relationship in which we have helped each other and discovered new things about ourselves because of the other. I can’t imagine a life without George, and I’m excited to introduce you to this intelligent, philosophical, creative, compassionate individual.

Note: The following interview was conducted via text message and letter. These methods were easier, cheaper, and more convenient for us than phone calls, since calls are limited to 15 minutes and cost $1.60 each.

Kat: We’ve talked a lot before about how the act of writing is transformative and often benefits the writer more than the reader. Tell us how writing has been therapeutic and healing to you, particularly in an environment that you’ve called a “warzone” and “constantly traumatizing.”

George: There’s a saying: “Idle hands are the devil’s playthings.” Writing gives me something productive to occupy my hands with, which helps keep me from getting caught up in the destructive behaviors common to prison life. Also, writing is a tangible way for me to process my past and present traumas, make sense of it, heal. In my head, it gets confused, jumbled. Paper gives me distance.

K: We’ve also talked about how the prison environment is intentionally dehumanizing, no matter the attitude of guards or other prison staff. How has writing humanized you?

G: To be a healthy human, especially in psychological terms, I believe we need to experience a range of things — joy, sadness, grief, excitement, anger, fear, shame, vindication, etc. A full life, with all its ups and downs, and our social interactions, allows a person access to that range of experiences — and, as a result, we can be more multidimensional, and our ability to truly empathize with others has all those points of connection.

Prison is dehumanizing by nature, in that it’s such a highly controlled, restrictive environment that we just are not free to experience a broad range of emotions. So, we’re essentially incarcerated both physically and mentally. We’re sort of buried in the negative end of the emotional spectrum. There’s an overabundance of sadness, loss, regret, frustration, anxiety, fear, guilt, shame, loneliness — but a lack of the positive emotions, such as joy, hope, enthusiasm, excitement, connection, etc.

Writing and reading are ways that I try to not only cancel out that dehumanizing effect, but also to claw my way toward the light. Through writing, I get to remember experiences I no longer have access to, which triggers a lot of emotions. Through reading, I’m able to empathize with people who are experiencing life in ways I cannot — I get to vicariously live through them. In these ways, I both maintain and cultivate my own humanity.

K: To what extent has writing enabled you to transcend your environment, or to swing the other way, enmeshed you in it, considering how much you’ve written about it?

G: In a sense, writing has both enmeshed me more in this environment. At the same time it helps me transcend it. “Enmeshed” because to write about it, I have to think deeply about it, really immerse my thoughts into every aspect that I can — which makes me feel almost a part of the very architecture of this place. But writing also gives me some distance from the dynamics at work in here because I take the position of observer as I try to document and make sense of prison life. As a result, it’s liberating because I am better able to live intentionally rather than become a product of my environment, slave to its whims and dramas. This place, the culture here, carries a lot of momentum, like a powerful current that’s difficult to resist. Writing helps me swim instead of just getting dragged along.

K: You’ve published a book of poetry, Interface, and have co-authored several other books of prose and poetry, as well as a smattering of individual poems, essays, and Christian devotionals. Tell us about your writing dreams and ambitions at this point.

G: I suppose my writing aspirations are multifaceted. Like all writers, I want to see nearly everything I write get published. More than that, though, I want my words to be truly impactful to readers. I hope they’ll walk away with either some practical wisdom and/or new knowledge or understanding about life and humanity. I also just want to keep creating new work, and hopefully be able to share what I consider beautiful even when writing about dark, painful, uncomfortable, or ugly topics.

K: You and I just finished a book of writing prompts called Digging Deep: Prompts for Self-Discovery, Healing, and Transformation, which will become available to prisoners with tablet access on the Edovo app through the Human Kindness Foundation. We truly had to dig deep during the writing of that book, since we not only wrote the prompts, but we each responded to the exercises we created to use ourselves as examples. What did you learn — about yourself, about the writing process, etc. — in writing that book?

G: Oh man, I could write a whole book in response to that question! First, this was a book that we conceptualized in principle without any real idea of what it would take to create it; it evolved and took on a life of its own along the way. From that, I learned to stay open and flexible with the form an idea grows into — don’t keep too tight of a grip on it or else you might smother it. That takes humility, for sure, because pride wants it to develop EXACTLY as I imagined and at my pace. But when it comes to true creative inspiration, it’s less about materializing MY ideas and rather more like a conversation between us and the creator from whom the inspiration came.

Writing and reading are ways that I try to not only cancel out that dehumanizing effect, but also to claw my way toward the light. Through writing, I get to remember experiences I no longer have access to, which triggers a lot of emotions. Through reading, I’m able to empathize with people who are experiencing life in ways I cannot — I get to vicariously live through them. In these ways, I both maintain and cultivate my own humanity.

K: What are you reading now, and what literary sources have contributed to your evolution as a writer?

G: I’m always reading a number of things at once. I keep a pile of books and mags! Bibles, poetry collections, lit mags, science and history journals, fictional novels — I read a bit from each every day. The only specific literary source that influences my development as a writer is Scripture, in that it defines my values, motives, content boundaries, goals, and so forth. But more generally, by reading a ton of poetry anthologies and lit mags, I’m able to find stuff I love — then, naturally, those pieces influence my style because I try to write to mirror the styles I love to read. If I don’t like to read it, why would I write it? Or inflict it on a reader?!

K: I know that writing and publishing can be hard for prisoners because they lack the resources — computers, the internet, and/or someone on the outside to help. Even finding places to send work via snail mail is difficult. And prisoners have to rely on sources like Poets & Writers magazine or word of mouth to find out about them. What do you find to be the difficulties of writing in/from prison right now?

G: You’re right, the practical aspects of writing and trying to get published are difficult from prison. For instance, I must write EVERYTHING by hand, and some of my pieces require dozens of drafts, literally. So, the very act of writing is physically laborious and time-consuming — and painful because I have arthritis in my thumb! But the most difficult thing, for me, is that I HAVE to rely on people out there to help me with typing, submitting, etc. I’m very independent by nature, so it kills me to be so reliant on others. But it’s impossible for me to create publishable manuscripts otherwise.

K: What resources do you hope prisoners who write will be able to access at some point in time?

G: Having limited access to a computer and internet would be transformative for incarcerated writers. But I just hope people in prison somehow gain a direct channel to publishers, so we don’t have to go through a middleman. While I’ve been fortunate to team up with reliable people out there — Beth, Tessie, you — most incarcerated writers are not as privileged. I hear horror stories all the time, like one guy whose “friend” ghosted him after an argument, so he lost access to all his work. He didn’t have backup files or copies. That’s a devastating blow!

K: What’s your favorite piece of writing — poem, prose, devotional, book, etc. — that you’ve ever written, and why?

G: Honestly, I don’t have a favorite. I’m probably cliché here, but because ALL my creations are precious to me, they each are my favorite in their own way — especially at the time I’m working on them. Further, because I strive to constantly grow as a writer, I find my taste subtly changing over time, so what I enjoyed two years ago may not feel so exciting to me today.

* * * * * *

You can find links to George’s books, published poems, speeches, and more at katbodrie.com/georgewilkerson. His next book, Bone Orchard: Further Reflections on Life under Sentence of Death, will be published by BleakHouse Publishing in January 2025. For writing and project updates from me and George, subscribe to my newsletter at katbodrie.com.

Judi & her Jeep

A poem by George T. Wilkerson

i.

in the early-80s teenaged Judi learned

to use Sun-In to transform her dishwater

locks and prospects into white wine

and candlelight. that shit was Jesus

in a bottle, some sort of miracle,

the way she talks. between her swaying hips

and hair hung down to there, Judi was known

to bend men’s gazes like a stiff wind

blowing through field grass. hell,

even after she passed their mothers

in age, men bought her beers in bars to stick

around a little longer. as if time had erased

her body, part-by-part, leaving only her

hair — still long, still light — now nobody

would look her way if she didn’t have her Jeep,

she says. Imagine the disappointment

on their faces when the cute young blonde driving past

in the virgin-white Jeep with pink trim

turns out to be a wrinkled grandma! i can

hear her bitter-yet-delighted cackle

when she texts hahaha I almost feel bad

for them!

ii.

her persona’s too large to carry on

strong thighs that get tired before she does

of sashaying across gravel parking lots.

Judi’s soul will always be a trailerpark

Barbie in cut-off jeans and braless tanktop.

simple and attainable by 54

her fantasy was to be seen — but not

in movies or gossip magazines — in a Jeep

she owned, like Daisy Duke’s, that Hazzard

girl. long before we had Facebook pages, she dreamed

of a metal avatar she could pour herself into:

trick it out with decals, pimp it

and let it take her place out there to continue

to hold the looks — even if only for seconds

til she passed

a body’s speed limits, trailing Elvis in the air behind her

from her speakers.

iii.

screw Daisy Duke. Judi wanted to

own a hardbodied soft-top Wrangler like her

but not be her. she dreamed of dreaming bigger

than Daisy — and having Daisy tattooed down both sides

of her hood wasn’t because of that girl

in booty shorts, but the flower and petal-plucking

game of insecurity she used to play: he loves me,

he loves me not. even the Nebraska-red

she’d always wanted was an ex’s

favorite team color — so screw him

and his passions too! Judi was tired of fucking

playing games that empowered stupid boys

to decide whether she existed

or not. she may have wasted her reputation,

time, and tautness before she hit

middle age, but Daisy was gonna keep her sexy

temple clean and timeless, her engine hot and fast

but untouchable except by a glance.

Daisy would be more Judi than Judi’s body.

Kat Bodrie is a poet and editor in Winston-Salem, NC. She is Book Editor for BleakHouse Publishing. Her poetry has appeared in North Meridian Review, Poetry South, West Texas Literary Review, Rat’s Ass Review, Poetry in Plain Sight, and elsewhere. She often works with incarcerated individuals on their creative pieces. Website: katbodrie.com

George T. Wilkerson is a poet, writer, artist, and four-time PEN award winner on North Carolina’s Death Row. He is author of Interface and Bone Orchard: Reflections on Life under Sentence of Death; co-author of Inside: Voices from Death Row and Beneath Our Numbers; and editor of bramble online and Compassion. His poetry has appeared in Litmosphere, Poetry, Prime Number Magazine, and elsewhere. See more at katbodrie.com/georgewilkerson.

Subscribe to see more guest posts from WRJ’s amazing contributors / Paid access includes editorial feedback for 1 poem each month and more.